How to rap your way out of cancellation

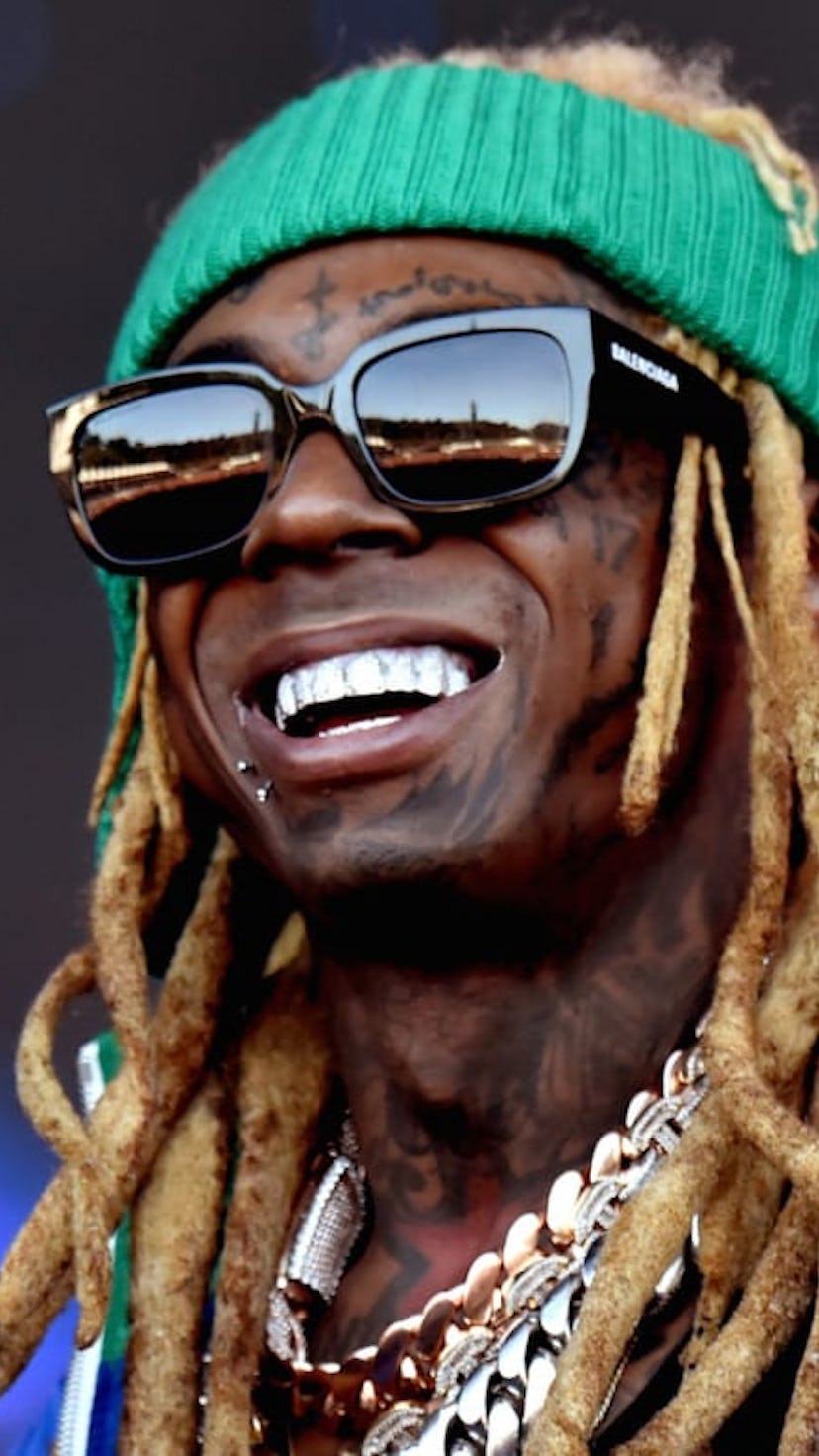

Artists like Lil Wayne and Kanye West don't deserve our attention, but their music always seems to get it.

Imagine the look on a future historian’s face when they come across an artifact like this photograph of President Donald Trump and Lil Wayne. Here is one of the all-time great rappers giving the thumbs-up alongside a man whose support among Black Americans sputtered in the single digits. For befuddled Lil Wayne fans, the October 2020 photo opp makes more sense months later when Wayne secured a presidential pardon for possession of a firearm by a felon. The hardest thing for future historians to parse won’t be why Lil Wayne embraced a racist authoritarian for his own ends, but why, less than a year later, we were back to praising his music.

Lil Wayne has been doing some of the best rapping of his career in 2021. Recent guest spots on songs like Tyler, The Creator’s “Hot Wind Blows,” Nicki Minaj’s “Seeing Green,” and Run The Jewels’ “Ooh La La (Remix)” harken back to Weezy’s creative apex from 2005 through 2008 when he created the modern template for rap superstardom.

His fans aren’t the only ones taking notice of his hot streak. Stereogum declared he’s “rapping like a legend again,” and the hosts on the Say Less podcast debated if Weezy was once again the Best Rapper Alive. While Wayne’s latest joint album with Rich The Kid, Trust Fund Babies, doesn’t reflect the superior rapping of his recent burst, the fact he’s able to release it with little backlash seems to be at odds with recent accusations of cancel culture going too far.

But did Lil Wayne really escape his past?

It’s important to remember the circumstances of the bizarre photo. In December 2019, Dwayne Michael Carter was arrested after law enforcement found a gold-plated handgun in his luggage on a private plane in a Miami-area airport. In November 2020, a month after the photo opp, he was charged with one count of possessing a firearm and ammunition by a convicted felon; he pled guilty and faced up to 10 years in prison. Trump pardoned Wayne on his last day in office, days before Wayne’s sentencing hearing was supposed to take place. (The president also pardoned Kodak Black.) Both artists were repped by the same lawyer, Bradford Cohen, a former Apprentice contestant who set up the photo opp and denied Lil Wayne’s endorsement of the president was a tactic for his pardon.

It’s easy to forget how a previous weapons charge from 2007 derailed Lil Wayne’s career. We can debate about when he stopped being the “best rapper alive,” but most fans can agree that by the time he finished serving an eight-month sentence on Rikers Island in 2011, he just wasn’t the same rapper anymore. “Jail has changed me forever,” he wrote in his 2016 memoir Gone ‘Til November: A Journal of Rikers Island, Post-prison, Wayne’s lighter flick remained one of the most exhilarating sounds in all of music—but it often felt more like a spark than a full-on flame.

In that context, Wayne’s endorsement of Trump can be seen through a purely transactional lens; he made a deal with the devil to avoid the hell of incarceration. This would align with most of Wayne’s political stances, which often seem entirely motivated by self-interest. His politics and art rarely intersect, typically in autobiographical blips like "Georgia Bush," a Dedication 2 mixtape cut where he righteously took President George Bush to task for mishandling Hurricane Katrina. Yet it’s unlikely he would have made that song if the storm had washed away any city besides his hometown.

Lil Wayne’s endorsement of Trump can be seen through a purely transactional lens; he made a deal with the devil to avoid the hell of incarceration.

At other times, Lil Wayne’s politics have come off as downright selfish. He once claimed there was “no such thing as racism” because are lots of white people at his concerts. He dismissed Black Lives Matter in an interview saying, “I am a young, Black, rich motherf-cker. If that don't let you know that America understands Black [redacted] matter these days, I don't know what it is.” His follow-up seemed to summarize his worldview. “I don’t feel connected to a damn thing that ain’t nothing to do with me.”

The calculated risk of standing with Trump makes sense considering the charges he was facing, but he’s weathered similar controversies and skated by with few consequences before: A few years after his comments about racism and BLM, his 2018 album Tha Carter V debuted at No. 1 and went Platinum.

Regardless of what Lil Wayne has said in interviews, what really matters is what he spits on the mic. Lil Wayne is, and always will be, a gifted wordsmith and a technical wizard. There are many imitators and plenty of artists he influenced, but there is only one Lil Wayne. Yes, he’s lost some of his commercial prowess, but not because of audience backlash; his struggles in the 2010s were typical of an artist decades deep into their career in the aftermath of a traumatic experience. But in 2021, if he continues to deliver a high quality version of his unique product, we’re likely to forgive, forget, or just move on because that's what our society does. We’re a lot more gracious to artists when their product is hitting.

Now consider the case of Kanye West. A handful of rappers endorsed Trump, but Kanye went far beyond. He didn’t just sport a red MAGA hat, he claimed it made him feel “like Superman.” Kanye’s third-party run for president was aided by Republicans and designed to help Trump win re-election. (If our future historian finds the Wayne/Trump pic weird, wait until they watch the video of Kanye’s off-the-rails White House visit.)

There was a deep sense of betrayal that the same person who said “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people” and whose music often addressed racism, would stan for someone whose initial claim to fame was his refusal to rent apartments to Black people. Many fans (this writer included) were ready to write Kanye off forever, and his politics made shunning lackluster albums like 2018’s ye that much easier. Unlike Lil Wayne, Kanye did face a palpable backlash. But just like Wayne, we were quick to move on.

After all of Kanye’s sins, once Trump was out of office and Kanye denounced him, millions of fans jumped at the chance to listen to DONDA. Being “canceled” led to listening sessions reportedly netting him millions of dollars, and some of the biggest opening-day streaming tallies in the history of Spotify and Apple Music, and the best first-week sales of any 2021 album besides Drake’s Certified Lover Boy. We haven’t forgotten what Kanye did, and he may not have earned our forgiveness, but he once again has our attention.

DONDA was still released under a cloud of controversy as critics balked at Kanye’s inclusion of DaBaby and Marilyn Manson. DaBaby’s recent struggles might suggest that there is a changing tide in how we hold artists accountable, but the tide was already turning on his music. Well before his homophobic remarks at the Rolling Loud Festival in Miami, fans were clowning him for using the same flows and the same type of beats. Like Kanye, DaBaby’s product was already in decline. His politics just made dismissing him easier.

We haven’t forgotten what Kanye did, and he may not have earned our forgiveness, but he once again has our attention.

While DaBaby did pay a financial price for his offense by losing gigs, he could have likely kept those gigs if he just delivered an apology video, like he said he would. Either way, it’s not some new wave of accountability; DaBaby losing checks because he said something stupid is not that different than when Lil Wayne lost a PepsiCo sponsorship after he spit a boneheaded Emmett Till lyric in 2013.

If you think we’re not going to forget what’s happening to DaBaby, consider that for all the flak he caught for being homophobic, he deserved as much for bringing out Torey Lanez at that same show—aligning himself with the man accused of shooting his frequent collaborator Megan Thee Stallion. If Kanye and Wayne’s examples have taught us anything, it’s that DaBaby can slide right back into the top of the game again in a year’s time—so long as he delivers a product we desperately crave.