For Black Iris Project, dance is a form of resistance

The Black ballet collective has taken on juvenile justice in a powerful new performance series.

The word “activism” often elicits a specific image, usually in relation to energized, chanting bodies filling a street for a march, linked arms gathered to block the outside of a government building, or people in suits and ties standing in a courtroom pushing for progressive policy. For Emmy-nominated choreographer Jeremy McQueen’s Black Iris Project, activism involves fluid movement and storytelling through multi-genre dance. Messages of resistance come in the form of back-to-back pirouettes and the South African gwara gwara dance, performed to the beat of hip-hop and fueled by unwavering truths about youth incarceration.

Black Iris Project, about six years ago, began tell stories about Black history and culture. They swiftly pivoted into addressing systems of oppression that touch Black and brown lives. Most recently, they’ve zoomed in on the broken juvenile justice system. “I am very, very unapologetic with my work and I make it very clear who it is for. My work specifically showcases Black bodies and highlights Black stories,” McQueen says. His collective has endured every barrier along the way, from financial strains to having their credibility constantly questioned. Some of their doubters, in fact, were from the dance community themselves, questioning the necessity of depicting this incarceration trauma.

McQueen says his primary goal is to show Black and brown people the beauty of how their lives can be reflected in art, and how matters that they care about can translate into performance. He’s intent on inspiring young people who may have never been exposed to ballet before, purposely leaving behind traditional European compositions and incorporating grounded, African-inspired body movements alongside the pointed toes and long lines characteristic of ballet.

Black Iris Project has received accolades from their believers and expressions of gratitude from individuals impacted by the prison system — responses that speak to the efficacy of using art to evoke both emotion and change. This type of advocacy, McQueen believes, is a vital step in forcing people to pay attention to our country’s festering incarceration problem.

Black American youth make up 41% of incarcerated juveniles — despite accounting for only 15% of the overall youth population. In this project, McQueen and his collaborators were intent on shedding light on real stories and pushing larger audiences to see this population’s humanity.

McQueen and his team have utilized their personal experiences as people of color in the often exclusionary world of ballet to fuel this work, gathering firsthand stories from educators and youth who have experience in the juvenile justice system, with the goal of creating a galvanizing and authentic experience.

When COVID-19 hit, the collective was ahead of the game when it came to alternative performance mediums, having already offered a recorded version of their work on public access television in 2018. McQueen’s 45-minute performance which was filmed in Langston Hughes’ old home, depicted a mother’s grief after losing her son to police brutality. Throughout the pandemic, they kept the momentum going by building up to a weighty, four-part project called WILD.

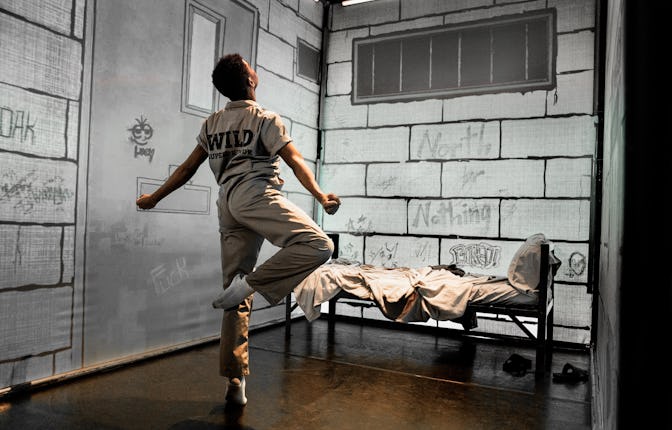

Loosely inspired by Maurice Sendak’s children’s novel Where the Wild Things Are, the series is multi-disciplinary experience (dance is still central, though). The project’s goal is to shed light on the ways our Black and brown community members are treated like animals through the prison industrial complex, as well as to promote healing and reconciliation for those who have survived the system and come out the other side.

In the opening of “These Walls Can Talk,” WILD’s second installment, a young Black man is pictured spinning his wheels inside a jail cell. He wakes up in the tiny cell to a guard forcibly removing his du-rag — a symbol of the ways individuality is repressed behind bars. Somber lyrics ( “they want me dead”) reverberate in the background over a heavy bass line, a melodic reminder of how incarcerated youth are forced to reckon with their lack of value within the system.

With the help of Citi Bike and Dance Lab New York, Black Iris project’s most recent third installment included a socially-distanced interactive performance where audience members participate in a bike tour. “Audiences in small groups were led throughout the various stops with a young person's story unfolding before their eyes,” McQueen tells Mic. “We created fictional stories inspired by real people, real events and circumstances, and it's been one of our most popular.”

On March 17, Black Iris Project will debut the stage adaptation of the four part installment at Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, as part of Carnegie Hall’s Afrofuturism festival. This adaptation will also be broadcast on television and available for worldwide viewing at the Black Iris Project’s website.

Over the past six years, Black Iris Project has pushed the boundaries of what we know as advocacy — and they’re nowhere close to slowing down. Moving forward, McQueen hopes to continue to create more dance experiences, in-person and virtually, acknowledging both the magic of live theater and performance alongside the necessity for accessibility.