It’s been 50 years since the Tuskegee Experiment. American healthcare is still racist.

Researcher Martin Tobin believes that revisiting the horrific "study" can help medical professional address today’s disparities.

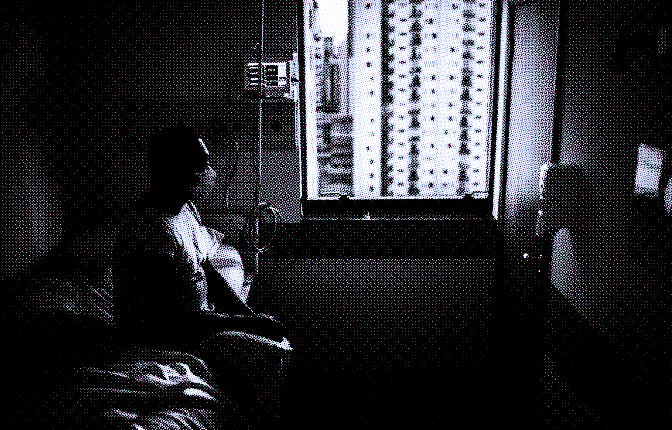

Fifty years ago, 400 Black sharecroppers in Tuskegee, Alabama were subject to a study that let 128 participants die at the hands of “science.” To put it bluntly, officials and trusted practitioners used Black men as guinea pigs in an experiment that would eventually be outed as one of the most racist, unethical practices in history.

In 1932, the CDC (then called the U.S. Public Health Service) launched the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Malem” which involved 600 Black men in total – 399 who had been diagnosed with syphilis and 201 who did not have the sexually transmitted illness. Officials never collected consent from participants, and many were told they were being treated for “bad blood,” rural terminology that covers various ailments.

The men were given free medical exams, free meals, and burial insurance as requisites for participating — but were not treated or given clarity on their diagnosis. According to records, 128 men died of untreated syphilis, 40 wives were infected, and the conditions of the illness are still deeply felt by the families of the men harmed by the study. In 1973, the study was finally deemed medically unjust and participants and their families settled a class-action lawsuit in 1974 as restitution for harms inflicted on the Black families who lost their fathers and sons.

While this sounds like a ghastly experiment we can chalk up to the racism of the time, it’s becoming exceedingly evident that this and other unethical medical “studies” have left a dangerous residue in today’s health care system. There is indeed a link between racism in the medical field today and one of its many roots, 50 years ago.

The lessons of the reality and ethics of the Tuskegee study are finally back in review. New research led by Martin Tobin, the pulmonologist, academic, and racial justice advocate, suggests that revisiting the details of the experiment could help people in the medical field better treat Black patients. Tobin examined findings from the 50 years since the unethical study and how it has impacted the field of medicine as we know it.

Examining this horrific event could shed light on how we can address medical mistrust and racial disparities in the field today. His unearthing of the details of the experiment speaks to why non-Black medical professionals especially have to make themselves aware of the past and become better advocates for justice. “You have these 400 men who had this injury done to them, and to not remember it is another form of injury,” says Tobin. While cultural misunderstandings about the Tuskegee study still exist, the study and its harms put the world on notice about what can happen in the dark when we don’t pay attention. “Scandal puts a face on the transgression,” he adds.

Examining this horrific event could shed light on how we can address medical mistrust and racial disparities in the field today.

To sufficiently cite how institutionalized racism has hurt Black Americans' health would take an entire book, but I can drop a few of the more egregious examples here. Black women's maternal mortality rate is alarming — partially because doctors often do not hear us. Black Americans' mental health is still very directly linked to racial trauma. The historical redlining of neighborhoods that resulted in food deserts can largely be blamed for a variety of bad physical health outcomes in our communities. And of course, as Tobin astutely points out, there is structural racism in place that prevents Black Americans from getting the best care possible.

And while it sucks that some Black and brown Americans don't trust the COVID vaccine enough to get it, the mistrust from these communities is absolutely justified. Who here would blindly trust a system that knowingly let their uncles and grandfathers die of a preventable illness — and a system whose trusted physicians conducted horrific experiments on their female ancestors?

Tobin tells me that all of us must face these stories so that we don’t replicate these harms in the future. “The three central lessons of the Tuskegee Study for researchers — and for people in every walk of life: the importance of pausing and examining one’s conscience, having the courage to speak, and above all the willpower to act,” he says.

“Science is at its best when it invites critical thought and makes room for meaningful dialogue and self-examination. Silence can be deadly,” the Eurekalert report on the study reads. “And, when scientists around the world failed to criticize the Tuskegee Study’s methods or question the integrity of the lead investigators, they jeopardized the integrity of the entire medical profession, contributed to the deaths of the participants, and extended the suffering of family members.”

These lessons are critical to how the next generation of medical professionals understand how they are serving their communities. “We must not let their contributions be taken in vain,” says Millard Collins, a physician and associate professor of family and community medicine at Meharry Medical College.

Collins points out that the Tuskegee study, outside of its communal harms, has helped develop protocols such as centralized internal review boards that require clear objectives and community involvement to keep studies ethical and safe. “Less than 3-5% of medical researchers are people of color so we still have much further to go but the Tuskegee study was a critical turning point for how myself and my students study medicine,” Collins says.