Inside the union push overtaking Starbucks

Employees from Buffalo to the Bay are organizing for better working conditions. We spoke to a few about why.

Our Streets is a column by writer and reporter Ray Levy Uyeda that highlights activists, artists, and organizers who are doing the work and reclaiming power for the people.

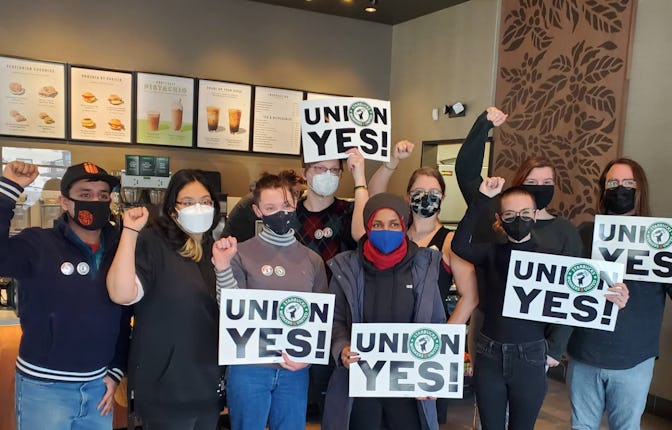

Across the country, workers at Starbucks are unionizing, demanding better pay and more transparency. A union drive that started in December 2021 at a single store location in Buffalo, New York, has now expanded to more than 60 stores across 19 states, with more and more workers excited at the prospect of negotiating a contract with a company they say has not taken adequate steps to protect baristas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It’s a prominent display of labor organizing for one of the most ubiquitous brands in the country (if not the world). Hundreds of employees working everywhere from Illinois to Michigan, Oregon to California to Wisconsin, are now vying to join their local affiliate of the Service Employees International Union.

Some workers say it’s Sen. Bernie Sanders’s (I-Vt.) influence that showed them what could happen if they fought to wrest control from the C-Suite. Other say they’re motivated by the fact that real wages haven’t risen in decades, and that the structures that are supposed to support low- and middle-income people are crumbling. The city council in Seattle, Starbucks’s home city, even passed a resolution supporting unionizing Starbucks workers.

“It's a job that is hard, but I love doing it,” 25-year-old Kasey Copeland, a barista at a Starbucks in Minneapolis, tells Mic. “With better wages, I wouldn't have to struggle as hard. I wouldn't have to work quite as many hours, and I feel like that would help me give my best even more so when I was there. I feel like we can make Starbucks better.”

This is a major moment for the 220,000 workers in Starbucks locations across the U.S. Lola Rubens, a 20-year-old barista in St. Paul, Minnesota, tells Mic that it comes as no surprise young people are at the helm. “There's this sense that the old systems that previous generations have adhered to aren't necessarily going to work for us and that we have to kind of pave our own way. And while unions are nothing new, they are definitely something that has fallen out of favor within the last generation.”

But, Rubens says, unions can bring workers “a step closer to equality in the workplace, which ultimately is the goal of a lot of this movement.”

So far, the unionizing stores are a fraction of the chain’s 9,000 locations. But Copeland says that customer support, as well as the push for workers’ rights across multiple industries, demonstrates that there’s a hunger to formalize worker power. She says that after the union vote at the Buffalo location, customers began coming into her store in Minneapolis and asking excitedly if that was going to happen there, too. Even Copeland’s congresswoman, Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.), has expressed her support of their union.

The pandemic has made the working conditions in industries that are customer-facing even more difficult. Low-wage workers have been forced to become public health officials enforcing mask usage. Infections on staffs have resulted in fewer people being asked to work longer hours to cover their coworkers’ absences. Copeland, who has coworkers who are immunocompromised or live with family members who are at increased risk of serious illness, says that any protections Starbucks offered at the beginning of the pandemic have faded away. In March 2020, her store had offered 10 days of isolation pay; now, she says, that benefit is no longer available due to changing CDC guidelines. She also tells Mic that workers are sometimes asked to return before they’re ready.

Reggie Borges, a spokesperson for Starbucks, tells Mic that store employees are guaranteed two rounds of “isolation pay” — pay for hours not worked during the five-day quarantine period recommended by the Centers for Disease Control — per quarter.

And then there’s the money. Copeland makes $16.28 an hour at her location, just $1 more than what she earned as a newly hired barista — three years ago. “They publicly are very progressive,” Copeland says of Starbucks, “but when it comes to actual social and material support to give to the baristas and everyone else, it really is lacking.”

She says that the corporation promised raises “soon.” Many of the wage bumps at her store have come in response to the whispers of the union — she thinks as a way to dissuade people from organizing — but Copeland says she and her fellow coworkers won’t be deterred. “The nickels and dimes that they're giving up now is nothing compared to what a union contract will win us.” (Borges told Mic that by the summer of 2022, the average wage for a Starbucks barista in the United States will be $17 an hour, with a wage floor of $15 an hour.)

“The wages that we negotiate will cover [union dues] tenfold.”

For Joe Thompson, who works at a Starbucks location in Santa Cruz, California, there is no reason workers shouldn’t earn a living wage — especially given that Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson took home more than $20 million last year, which was a 39% bump from his 2020 compensation.

Thompson, who’s in their first year of school at University of California at Santa Cruz, relies on wages from Starbucks to cover living expenses. On average, a living wage in California for a single person without children would be $18.66 an hour, or as high as $28.00 in cities like San Francisco. Thompson is currently making $20.67.

As shift lead at their location, Thompson has also taken on the responsibility of educating their coworkers about what a union actually is, as well as to expect now that they’ve gone public with their union drive. There were a lot of rumors in the earlier months about things like union dues — a regular union-busting line used to scare people out of unionizing by saying that the small fee paid to the union would bankrupt employees. In reality, union dues are 1-2% of hourly pay, and more importantly, “the wages that we negotiate will cover them tenfold,” Thompson says.

Working conditions, low pay, and the pressures of the pandemic have resulted in a prolonged mental health crisis among most young people, and Thompson sees that firsthand at their store. Thompson says that it’s not uncommon for employees to work even while experiencing a crisis. For instance, they tell Mic, a coworker was “having a panic attack in the back of house, and straight up, they just continued working afterwards. And my first thought was like, ‘That is quite literally a medical emergency happening.’” Thompson hopes that negotiations will result in one dedicated mental health day per month in addition to what the company already offers, which includes access to a mental health app and some free counseling sessions.

“We respect our partners’ right to organize,” Borges, the Starbucks spokesperson, tells Mic. “We don’t believe a union is necessary, but we understand their point of view. In the instance that they file petitions, we’re going to respect the process.”

Rubens, in St. Paul, disagrees with Borges’s statement. She’s heard the rote assurances that lines of communication are open between workers and corporate, but feels that even if corporate is open to hearing feedback, it “does not necessarily mean that they're listening to what we have to say.”

The biggest irony in all of this is that Starbucks insists on referring to employees as “partners,” Copeland says. “They don't take the time to talk with us and understand [us] and treat us like partners,” she tells Mic. “What kind of partnership is this? You know, we do so much for you, we uphold these missions and values, we make the ‘third place’ that you brand yourself around. And what are we getting in return?”